Universal History Archive

Where should we go? The Moon or Mars?

There’s been a lot of excitement around space exploration recently. Astrophysicist Paul M. Sutter discusses the viability between the Moon and Mars.

Space is sexy again. After the excitement of the initial Apollo missions dwindled into a subject only discussed by ultra-nerds, and the cool factor of the Space Shuttle gave way to the realization that it didn’t really do much, people generally lost interest in space.

But now we’re back at it again, and this time…we mean it.

Private companies like SpaceX are gearing up to send Starships (and I’m not using that word as some sort of over-wrought metaphor, they are literally naming their next generation of rockets the Starship) to Mars. Then there’s NASA, who’ve recently announced the Artemis program with the goal of sending the first woman and the next man to the Moon, in hopes of laying the groundwork for continued human habitation on our little grey satellite.

But we can’t go everywhere in the solar system simultaneously, at least not this generation. With limited time, money, resources, and interest, what should be our next major goal in human space exploration?

Universal History Archive

A chapter of the layered geological history of Mars is laid bare in this postcard from NASA's Curiosity rover. The image shows the base of Mount Sharp, the rover's eventual science destination.

“Mars” is easier to say than do. Yes, it has all the temptations: whoever first sets foot into that red dirt will be the first human to walk on another planet and surely something that will end up in the history books right after the entry for Armstrong. And Mars has some things going for it that the Moon doesn’t: more water (it’s frozen, but it still counts), more gravity, and more…redness.

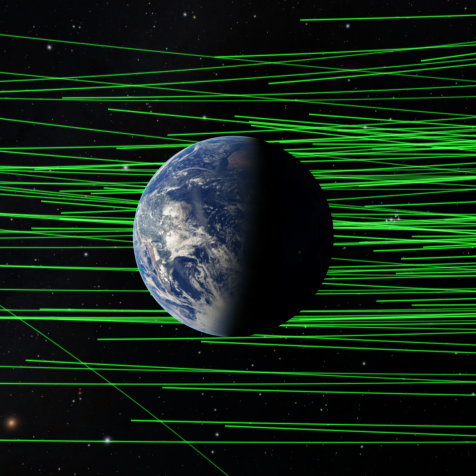

But Mars is far away. Like, really far away. Because we have to wait for the orbits to line up just right, the minimum length for a there-and-back-again mission to Mars is about 18 months. 18 months of weightlessness. 18 months of only a thin sheet of metal between you and the vacuum. 18 months of isolation from the rest of humanity.

NASA

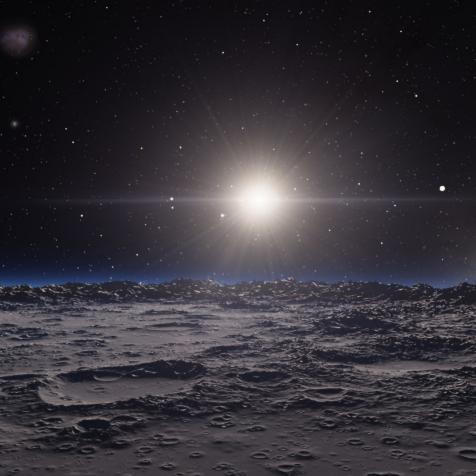

10th July 1972: A close-up picture of the moon taken from Apollo 16.

On the other hand, we have the Moon. Nice, close, and accessible Moon. It’s so easy to get to the Moon that we’ve already done it, back before we had cell phones and internet. Seriously, we figured out how to land on the Moon just a couple decades after inventing two-ply toilet paper. You can hop on a Starship, awkwardly bunny-skip across the Moon, and be back by the end of the week. If something goes wrong, help is only a day or two away.

And yet, it’s easy. Why should we invest billions of dollars in accomplishing things that our ancestors already did?

But space is hard. Distance is hard. Time is hard. Getting Mars and back is frighteningly hard. We don’t have the technology right now to get us safely to Mars and (more importantly) safely back. We’ll have to work as hard as we can for decades before solving all the engineering and technical problems. They’re not insurmountable, but they’re real.

And because orbits are orbits and launch windows are launch windows, we only have a couple chances every year to try for Mars, whereas with the Moon we can give it a (moon)shot basically every day. Our current knowledge of how to live and work in space is based on decades of try-and-try-again, testing techniques over and over until they become routine. Will we have enough chances for a successful Mars mission before funding and/or passion dries up?

We can certainly get to the Moon much faster than Mars, but will those missions ignite as much curiosity and drive as a push to the red planet would?

It’s hard to say. But whatever we do, let’s get off this planet and try something new.