Dotted Hippo

Why Does Pluto Have Such a Weird Orbit?

Pluto is the black sheep of the planets in our solar system and it looks like astronomers aren’t sure how long Pluto will remain in its present orbit.

Back in the day, before Pluto got demoted to dwarf planet status, we learned that our solar system had nine planets. Eight of the planets had nice, neat little orbits that are nearly circular and all in a tidy little plane.

And then there was Pluto--the oddball, marching to the beat of its own orbital drum and doing whatever the heck it wanted. Apparently it was too distant from the sun for anyone to bother correcting it and make it act like the planet that it was supposed to be.

For starters, take its inclination, which is the word astronomers use to describe the tilt of a planet’s orbit. Relative to the average of the rest of the planets in the solar system, Pluto orbits at a jaunty angle of 17 degrees. This doesn’t sound like much until you compare it something like the Earth, which is a mere 1.5 degrees off. In fact, you can compare it to any other planet that you feel like and you’ll get the same result: the planets of our solar system do this, and Pluto does that.

And then there’s the eccentricity. Planets don’t orbit around the sun in perfect circles, but in stretched ellipses. The amount of stretchiness of that ellipse is called, as you might have guessed, the eccentricity. An eccentricity of 0 indicates a regular circle, while an eccentricity of 1 means you’re in big trouble: your orbit has stretched so much that you’re on an escape trajectory from the solar system altogether.

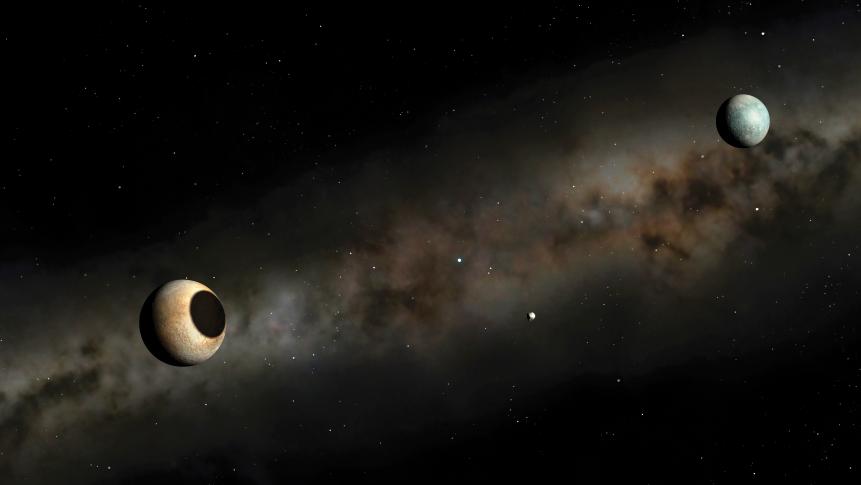

The Earth is a good little planet, with an eccentricity of only 0.016. Amongst the rest of the planets, the worst offender is Mercury with an eccentricity of 0.2. And Pluto? Well, to call Pluto eccentric would be an understatement. With an eccentricity of 0.25 (in other words, ¼ of the way to complete removal from the system), the stretchiness of its orbit is so exaggerated that it spends 20 of its 248-year orbit within the orbit of Neptune.

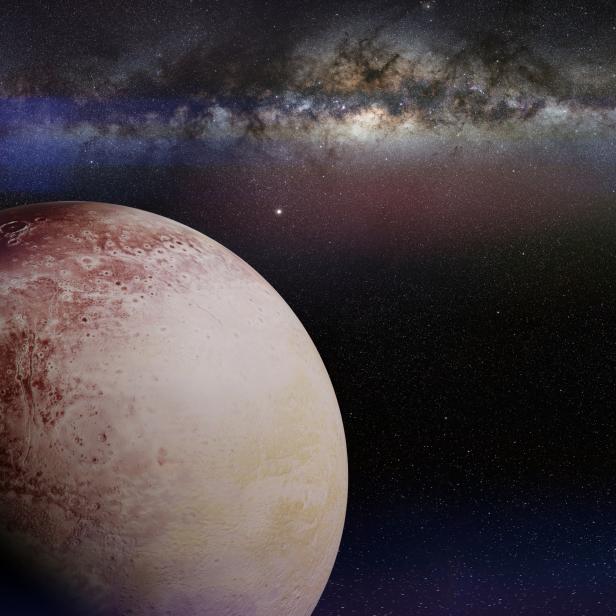

MARK GARLICK

Pluto’s orbit is prone to destabilization, but sometimes Neptune manages to calm it down. The two worlds are (for now, at least), locked in something called a resonance, where the period of one orbit is a simple multiple of the period of another orbit. In the case of stately Neptune and rascally Pluto, for every three orbits of the little odd world, the stately giant does two.

This resonance keeps Pluto’s orbit regular (as weird as it is) over the course of millions of years. But things aren’t very stable over long time periods in the outer solar system, where the gravitational influence of our sun is nothing more than a passing flirtation. Astronomers aren’t exactly sure how long Pluto will remain in its present orbit – there are too many complexities to account for to build an accurate picture past 5 million years or so. There’s a decent chance that our distant descendants will wake up one day to find Pluto striking out for a journey amongst the stars…or crashing headlong into the sun.

Like I said, Pluto does what it wants.

#TeamPluto premieres Tuesday, February 18th at 11pm ET/PT on Discovery and Discovery Go.